"History" - empire and subjugation

Much of our history (as opposed to “pre-history”) makes a depressing story. The bloody skirmishes of the Dark Ages; the civil wars (with Thomas Hobbes observing that life can easily degenerate into something “nasty, brutish and short”); the rise of empire and slavery, fuelling William Blake's “dark satanic mills” of the Industrial Revolution; mass dislocation of people from their homes and the landscape; the World Wars of the 20th century; any sane person would conclude that both the land and its people would end up exhausted.

2000 years ago, the Romans tried to impose Empire on our islands for perhaps the first time. The brighter news is that, not for the first nor the last time “cultural absorption” took the edge off a foreign elite.

Less than a thousand years ago we saw the beginnings of the British Empire, with the Norman invasion of 1066 (and all that). Here was a step change in society. Before this time, in the “Dark Ages” families, villages and districts assembling at the Viking “tings” or the Anglo-Saxon “folkmoot” for collective government, facilitated by sophisticated “laws” about procedure and decision-making. Now there was to be a rigid hierarchy backed up by ruthless martial law.

The Normans were particularly brutal with their subjugation of the areas around York, Bradford and other northern towns. Villages and crops were burned and the local population slaughtered. As part of this “ethnic cleansing” strategy, the stronger of the Viking chieftains were paid to leave. Vast areas of land were given over to powerful Norman families, who based themselves in wooden forts at first, then later in stone castles which were to dominate the physical and political landscape of the north of England for hundreds of years.

The Scots, by virtue of of their difficult territory (and some would say their difficult temperament), refused to submit to the Normans. They were, of course, assisted by logistics, as they had been against the Romans - the further north the would-be conquerors went, the more their supply lines became stretched and the less hospitable was the climate and the landscape.However, the threat from their southern neighbours was to push them towards a similarly baronial and nationalist future.

Scotland was a part of Norway before it ever achieved nation status in its own right. Indeed for a short period Norway was ruled from Orkney. Around the 1000AD Scotland came into being as a recognised country. Malcolm Canmore made definite attempts to extend and consolidate land under his control. This brought the Scots into conflict with the English for the first time as the Border was pushed South from the Forth to the Tweed and beyond.

After nearly 200 years of harassment and counter-attack, the Scots were finally able to assert their independence as a nation by defeating the army of King Edward 1 of England at the battle of Bannockburn in 1314. This was followed in 1320 by the Declaration of Arbroath: a document comparable to the Magna Carta in establishing ideas of freedom and democracy within a nation state. The declaration also contains a reference to the celtic origins of the Scots that agrees very well with recent evidence about the early settlers.

For several hundred years afterwards, “freedom” would often mean swearing allegiance to the local Lord and hoping for some protection in return. For much of our history, ordinary people would keep their heads down, pay their taxes, and most men would try to avoid being forced into the military. This is not very exciting stuff, so even the invention of writing, and then the printing press, has left little record of the history of the “commoners”.

In spite of the best efforts of the Normans, “history” was left to the powerful families who ruled entire regions, slugging it out in ventures such as the Wars of the Roses to see whether they could get their hands on the nation's crown, its army and its treasury. Like the Romans before them, the Normans remained a colonial elite. They added to the English language rather than replacing it, and they hardly contributed to the English gene pool at all.

Ironically, the Scots aristocracy would increasingly look towards France for support, allowing a whiff of the other “gallic” to float around the growing cities like Edinburgh.

Meanwhile, in the wilder and more inaccessible areas of the land, powerful families ran free of state control. The rievers of the border-lands (both English and Scottish) would raid each other's territory and also otherwise calm areas, causing havoc among the villages, and this cattle-rustling and gangsterism would continue almost through to unification in 1707.

“... for, as long as but a hundred of us remain alive, never will we on any conditions be brought under English rule. It is in truth not for glory, nor riches, nor honours that we are fighting, but for freedom -- for that alone, which no honest man gives up but with life itself.”

Declaration of Arbroath 1320

Along with the growth of the nation state, the Christian church was becoming more organised. Monasteries, originally collectives of hermits, were established by the early Celtic chirch on remote islands, as if to emphasise their other-worldy and spiritual role. As the years went by, Lindisfarne became one of the main centres of European culture with links to the courts of King Alfred in Wessex and the Emperer Charlemagne in Aachen. Unfortunately, Lindisfarne bacame an accessible target for Viking raiders. The hand-wrought Linisfarne Gospels survived the attacks until the late 9th century when the now-pricelass manuscripts were nearly lost at sea by monks fleeing another "smash and grab". The Vikings did not seem to place much value on books.

But monasteries grew in size and wealth, and became important centres (sometimes the only centres) of literacy and learning. In turn this would lead to the establishment of universities: St Andrews University was given its charter in 1410 as a school attached to the Augustinian Priory. It was lucky that this was done, because the Cathedral and the rest of the church establishment was stripped out in 1559 during the Reformation.

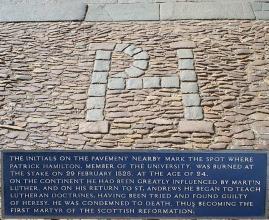

The Reformation in England had started earlier, in 1536, precipitated by Henry the Eight's argument with the Pope over his divorce. For hundreds of years “church and state” had been a valuable counter-balance to absolute power. But now the monasteries were seen to be threatening the state, and the men of the church were widely seen, particularly by poor people, as bloated money-grabbers. Animosity was stirred by protestants such as John Knox. In St Andrews you can see the pavement memorials to protestant “martyrs” with mosaics now showing where their blood soaked into the cobbles. In the Dark Ages, people were fighting and killing each other over land. Now, in a worrying development, they were beginning to fight over ideas.

Click to read the plaque for the Patrick Hamilton memorial.JPG

Click to read the plaque for the George Wishart memorial.JPG