North Britain: settlement, exploitation and Big Ideas

What is North Britain? I live here, so I just need to look around me. And perhaps remember what the older members of my family have told me, reflect on what I learned at school, do a bit more research ...

Observation is one of the most important skills that we learn in our permaculture training. Most of us need lots of practice in this, and these days I get simple enjoyment from "seeing how the land lies". And I find it useful to look at the big picture as wells as the small details. I let my focus drift, I set aside any fixed ideas that I have.

The observation, and my reflections, that I outline here are about an entire region that my colleagues and I call "North Britain". I hope this small exercise will be the start of a bridge between the global, conceptual aspect of permaculture design and the local, practical application on our "home turf". At the Institute, we have a sense of shared work: there are some important jobs to do. If we are to re-integrate ourselves with the landscape, and live lightly on the land, then we need a good grasp of who we are, where we are, and what the land can give to us.

t's easy to lose our sense of place in the modern, sophisticated world of today. I am fortunate that much of my life has been spent either living or roaming around in North Britain. It is my home, and I would like to see it in a better state.

Our main challenge is to act within the "third ethic" of permaculture - to live within the limits of what the land can provide. The whole of the British Isles regenerated itself after being covered in ice 20,000 years ago. This story is about how we settled in that wilderness and how we went on from those exciting beginnings.

This is my first attempt at telling the tale. I look forward to others, more eloquent than myself, to take the observation further. It is an important story, and it need to be told. All stable societies have their creation myths, a sense of where they come from. They have a relationship with their home landscapes and a deep understanding of the natural world around them. It is even more important because, as the philosophers say, those who cannot learn from the past are condemned to repeat it.

Some regions of North Britain

Lancashire and Cheshire

The Lake District

The Isle of Man

Galloway and south Ayrshire

The Atlantic coast to the north of Glasgow, including the Western Isles

Inverness and the far north

Highland Perthshire

Morayshire, Aberdeenshire, Angus, Tayside

The Kingdom of Fife

The Central Belt

Lothians and Borders

Northumberland and Durham

The Yorkshire Dales

The East Riding,

South Yorkshire and Lincolnshire

The Yorkshire "Woolen District"

The Peak District

Deep time

At one time, Scotland was separate from England. But that was about 400 million years ago, in the Silurian period. In a large-scale ultra-slow-motion collision, two massive continents crunched into one another, altering the face of the planet. The Pennines and the Lake District were thrown up from the bed of the ocean that was squeezed out of the way. Cracks in the earth's crust allowed huge magma flows to ooze out, and then cool, to add further interest to the landscape.

Fortunately, perhaps, we were not around to witness it, We were just a twinkle in Evolution's eye, and it would be nearly 400 million years before we arrived to set up home in the wreckage. Meanwhile, successive Ice Ages, and the rivers in the inter-glacials, formed the landscape of today, grinding and gouging, lifting and depositing as they came and went.

So, here we are today, in the northern areas of the island that was named “Albion” in Roman times, and later “Britannia” after the Britons who had settled here before, and during, the Iron Age. We live in a cool, sometimes cold and wet, outlier to continental Europe, where warmth has often meant family, fireside, songs and stories. It is natural that we now prefer to downplay our recent history of kings, nation states and empire and seek instead to revive the stunning beauty that used to surround us all. It is in celebration of our rich cultural heritage, enlivened by millennia of “immigration”, that we trace our way back to those early settlers who named their wild new home “Priten”.

Geology

The Solway Firth lies over a major fault line in the earth’s crust, the Solway Line. This marks the boundary between two ancient continents: Laurentia in the north and Avalonia in the south. They collided long ago creating the Scottish Southern Uplands and uniting the land masses of Scotland and Englandt. By contrast, ancient volcanic activity created the distinctive hills around the Forth and Tay such as Dundee Law, North Berwick Law and Arthur’s Seat in Edinburgh.. Read more.

Over to the East the resulting Great Whin Sill provided an natural foundation for a large section of Hadroia's Wall.

The oldest rocks in the Pennines are Ordovician in age (about 480 million years old). They were deposited along the edge of a thin continent called Avalonia (which consisted of England and Scandinavia) that lay near the south pole. It was an archipelago similar to Indonesia today. Slowly, during the Ordovician and Silurian (about 480 to 420 million years ago), Avalonia drifted northwards. Sediments were washed from the continent into the sea along its northern margin. These sediments now form the Ordovician and Silurian rocks, outcrops of which can be seen in the Fells and the Lake District. Read more.

Examples used include Volcanic Ash, Columnar Basalt, Quartz Dolerite, Olivine Dolerite, Andesite, Oil Shale, Tree Root, Algal Limestone, Massive Limestone, Red Devonian Sandstone, Shelly Limestone, Rippled Sandstone, Coral limestone, Conglomerate, Coal, Dolomitised Limestone, Cross-Bedded Sandstone, Felsite, Fossil Rootlets, Agate Rich Andesite, Crinoidal Limestone and Highland Schist!

North Britain - a region of Europe

The northern part of the island that the Romans called “Albion” runs from the southern extent of the Pennine Hills, in the Derbyshire Peak District, up to the Orkney and Shetland Isles lying off the north coast. North Britain contains the greater part of upland Britain and has an extensive coastline with many off-shore islands. The coast of Argyll, one of the regions on the west coast, is said to be longer than that of France. Shetland has 900 miles of coastline.

When it comes to human settlement, the regions of North Britain can be defined in many ways. We can make a case for four or five distinct regions in both Scotland and in northern England, with the many of the islands, such as the Isle of Man expressing further, unique identities.

Rivers have been often been used to define regional boundaries,, but this approach has little relevance in modern life. As a traveller, the only sense of transition that I get is when I cross the hills, using one of the numerous routes across the Pennines, or travelling across Rannoch Moor. The sense is strongest at Carter Bar, with the possibility of great views across the Borders and a steep, but largely hidden, descent into Northumbria. But the modern tourist industry has designed the crossing to look like a border post.

To be fair, for many years it was the site of the annual tryst where the English and the Scots Lairds of the Marches met with their men to settle outstanding grievances under the rough laws of this wild landscape.

I remember from my childhood that it was just a place to stop for some fresh air, and a bit of a pic-nic. But now when I stop there, I sense the transition of the high pass and I think of many other "summit" areas where competing families could have met in "no-man's land" to prevent the worst excesses of territorial rivalry.

Beattock has even more of the mountain pass about it, with Glasgow beckoning to the north and empty border lands to the east and west, and down the valley of the Eden to Carlisle

The hard road from Carlisle to Hawick, passing by the grim Hermitage Castle on what is now the A7, similarly takes us through a landscape where sheep outnumbered people many times over, and they and the hardy cattle were the currency of generations of rievers. Over generations this land was ravaged by the territorial ambitions of Scots and English kings, queens and nobility.

The main split in North Britain is not north-to-south, but east-to-west. The uplands form the natural barriers. The populations of Barnoldswick and Todmorden have become apoplectic in the past at the slightest hint that a boundary line on the map might be altered. Sometimes it is difficult to believe that the Wars of the Roses were over 500 years ago.

Further north, the cultural differences become more distinct and go further back into history, resulting in Scotland having at least three languages: Gaelic (related to Irish), Brythonic (nowadays sometimes named "Old Welsh") and variants of Anglian (both "Scots" and "modern English") deriving from Middle English.

The western parts of the country have a rich celtic heritage, with the Gaelic being one of Europe's oldest languages.

The Brythonic languages, once prevalent in Galloway, Cumbria, the Borders and further east died out, and it has been suggested that some of the ‘British tribes’ left for North Wales, filling the vacuum left by the demise of Roman settlers, and contributing to the marked differences between North and South Welsh. There is also speculation that eastern tribes such as the Picts had languages in this group.

In the east and south the Scots tongue shares many words with modern Scandanavian languages and carries germanic patterns of speech, Known north of the Tay as “the Doric” (after the Greek for “country-folk”), and in the Borders and in the Central Belt (including the Lothians and Fife) as Lallans, (Lowlands) it is the mother tongue of Robert Burns and is closely related to the dialects of Anglian in Northumbria. The distinct nordic and germanic influences push at the line between a dialect and a distinct language, as English readers of Burns will know.

Similarly the dialects of Yorkshire, Lancashire and Cumbria are influenced by Scandanavia and the landscape studded with nordic place names all the way up into the high hills.

Local difference and a strong sense of local identity remain marked characteristics of North Britons, be they English or Scots, to the extent that many immigrants have learned to respect the same differences.

Fair fa’ your honest, sonsie face,

Great Chieftan o’ the Puddin-race!

Aboon them a’ ye tak your place,

Painch, tripe, or thairm:

Weel are ye wordy of a grace

As lang’s my arm

The groaning trencher there ye fill,

Your hurdies like a distant hill,

You pin wad help to mend a mill

In time o’need

While thro’ your pores the dews distil

Like amber bead

"Ode to a Haggis" - Robert Burns

- If hosen and shoon thou ne'er gav'st nane

The whinnes sall prick thee to the bare bane.

- From Whinny-muir when thou may'st pass,

To Brig o' Dread thou com'st at last;Lyke Wake Walk

(Traditional, NE England)

Dhannsainn is ruidhleadh mi

Air oidhche banais Mór a'Cheannaich

Dhannsainn is ruidhleadh mi

Air oidhche banais Mórag

Dhannsainn is ruidhleadh mi

Air oidhche banais Mór a'Cheannaich

Dhannsainn is ruidhleadh mi

Air oidhche banais MóragTraditional Puirt A Beul, via Capercaillie

Early settlers

Colonisation by us humans began around 14,000 years ago, once things had warmed up enough after the Ice Age and the tundra had thawed out sufficiently to allow tree cover to return.

If there were hominins living in Britain before the latest Ice Age, they spent the winter in south western Europe, just like some of their wealthier modern counterparts do today. But their “winter” was to last several thousand years. These Iberian shelterers have been identified as Celts. As soon as the climate improved, some of them took to their ships and colonised the west of Britain. Genetic markers show that these early settlers have had a big influence on the current population. Meanwhile the Gaels (possibly originating in Asia) moved through central into western Europe, bringing other “celtic” languages and cultures with them.

7500 years ago, immigrants were still walking into the region across what was to become the bed of the southern North Sea (Doggerland) and the English Channel. The sea levels were to rise a further 3 metres over a few hundred years soon afterwards, inundating mesolithic settlements off the coast of southern England and the Isle of Man. This was caused by a relatively small pulse of ice melt-water. In the previous 7000 years there had been two step changes in sea-level, each with a magnitude of the order of 20m, as the planet re-adjusted from the weight of massive ice sheets, and the resulting flow of meltwater into the seas. Following this third sea-level rise, we were collection of islands, and the sea was to figure more strongly in our cultures.

The western Celts probably arrived by sea and colonised Hibernia, the isle of Man and western Scotland. As anyone who has read Sellers and Yeatman will know, the “Scots” originated from Ireland. (It is likely that these folk never called themselves “Scots”, but were named by the Romans as “outsiders” or “raiders”). Meanwhile, the Gaels came in from central Europe and ended up in Wales, Cumbria and, possibly, Galloway. They spoke a form of gaelic that is now called brythonic, as distinct from the goldelic languages of their western cousins. The Romans wrote about them living in the Borders and Lothians.

Meanwhile, the Picts had settled in the north and east of Scotland. Even in the dark ages after the Roman invasion 2000 years ago, the Picts produced beautiful stone inscriptions depicting people and landscape, There is not much that remains of their culture apart from these richly decorated, but indecipherable, carvings. Even their original name is a mystery, they were named “Pictii” (the painted ones) by the Romans. Their language is lost, but was probably brythonic and related to the Welsh and the tribes in the east of England such as Boudicca's Iceni. By the time of Bede 1300 years ago, pictish was identified as a language distinct from gaelic and welsh, leading to the intriguing possibility that it was influenced by contacts with invaders from across the North Sea. In the end, the Picts were to lose their identity through these invasions, and were subsumed into the wider population around 1000 years ago.

"The Scots (originally Irish, but by now Scotch) were at this time inhabiting Ireland, having driven the Irish (Picts) out of Scotland; while the Picts (originally Scots) were now Irish (living in brackets) and vice versa. It is essential to keep these distinctions clearly in mind and verse visa."

W C Seller and R J Yeatman

1066 and All That: A Memorable History of England, comprising all the parts you can remember, including 103 Good Things, 5 Bad Kings and 2 Genuine Dates

Trade and technology

Long before the Roman invasion, 4000 years ago, bronze-making technology arrived from mainland Europe, possibly along the iberian connection and through the other immigration and trade routes operating at the time. Civilisation was on the rise in the middle east and trade was already important for keeping up with the latest technology. Bronze is made from copper and tin, and the two minerals were rarely found anywhere near each other. With good transport and trade links, metalworking was soon an established craft and this speeded up the tree-felling that had started in Neolithic times.

The Iron Age in began around 2500 years ago. Agriculture had begun to drift in from mainland Europe around 6000 years ago and can be tracked by the spread of the rectangular long-house (up to then, our dwellings had been round-houses). There is also archaeological evidence that the rapid conversion to agriculture led to a decline in human health. But the arrival of iron was to speed the introduction of agriculture. The new technology provided stronger ploughs, as well as tougher axes and led to inevitable improvements in weaponry used to secure and steal land to feed a growing population.

Over 2000 years later, the art of metal working would meet other innovations in North Britain in a convergence that would bring about the "advanced" world that we know today. (As a small example, the modern plough was developed in Berwickshire). But both agriculture and large-scale war would be slow to take hold in our corner of Europe; it was society that was clearly developing here. The Bronze Age and Iron Age technologies and cultures ask interesting questions about the extent of the immigration of people, set against the migration of ideas. But history shows that our bleak and windswept region was still attractive to those who were living in even harsher environments.

1200 years ago the Vikings arrived in Orkney and began to settle in the region, establishing a parliamentary assembly at Tingwall in Shetland. There is some debate about whether they killed off any original Pictish inhabitants or whether there was some accommodation with inter-marriage. (In a parallel case, genetic research in Iceland has recently proved that Icelanders are more Irish than Viking). Although they had a fierce reputation, most of the Vikings could turn their skills to farming, sailing and trade. Well organised, but with a sophisticated tribal culture, they arrived at the Isle of Man and established Tynwald, the Isle of Man parliament that is still in place today, making it one of the oldest unbroken parliaments in the world.

The Vikings also settled in Orkney and Shetland, giving the name Sutherland to the northenmost part of mainland Britain. Even more confusing to us southerners, they named both of the largest islands of Orkney and Shetland as "mainland". They sailed even further south and established a successful trading port at Dingwall, at the head of the Firth of Cromarty, not far from Inverness. Having negotiated with the Scottish chieftains, the Vikings were allocated any land that they could sail round, leading to some spectacular boat-dragging across dry land on various peninsulas, often leaving the norse place-name “Tarbet” or “drawboat” to commemorate the feat.

Around 50 years later, and even further south, the Vikings took over York, which had been developed as a city by the Romans and then the Anglo Saxons. Having mastered both agriculture and metalworking, the Vikings could lay claim to be the most “civilised” people in northern Europe. With boundless entrepreneurial energy, and the best technology they could lay their hands on, they invested heavily in their new asset to turn it into a world-class trading centre. They were, perhaps, too successful as pre-medieval city-builders, and they, too, were soon to be the subject of a take-over.

Both genetic studies and historic literature suggest the Vikings had a much greater influence on North Britain than the Romans or other invaders from the south. They were feared as warriors, but they were skirmishers and traders, rather than empire-builders. They would leave attempts at that last and dubious activity to their cousins, the Normans.

"History" - empire and subjugation

Much of our history (as opposed to “pre-history”) makes a depressing story. The bloody skirmishes of the Dark Ages; the civil wars (with Thomas Hobbes observing that life can easily degenerate into something “nasty, brutish and short”); the rise of empire and slavery, fuelling William Blake's “dark satanic mills” of the Industrial Revolution; mass dislocation of people from their homes and the landscape; the World Wars of the 20th century; any sane person would conclude that both the land and its people would end up exhausted.

2000 years ago, the Romans tried to impose Empire on our islands for perhaps the first time. The brighter news is that, not for the first nor the last time “cultural absorption” took the edge off a foreign elite.

Less than a thousand years ago we saw the beginnings of the British Empire, with the Norman invasion of 1066 (and all that). Here was a step change in society. Before this time, in the “Dark Ages” families, villages and districts assembling at the Viking “tings” or the Anglo-Saxon “folkmoot” for collective government, facilitated by sophisticated “laws” about procedure and decision-making. Now there was to be a rigid hierarchy backed up by ruthless martial law.

The Normans were particularly brutal with their subjugation of the areas around York, Bradford and other northern towns. Villages and crops were burned and the local population slaughtered. As part of this “ethnic cleansing” strategy, the stronger of the Viking chieftains were paid to leave. Vast areas of land were given over to powerful Norman families, who based themselves in wooden forts at first, then later in stone castles which were to dominate the physical and political landscape of the north of England for hundreds of years.

The Scots, by virtue of of their difficult territory (and some would say their difficult temperament), refused to submit to the Normans. They were, of course, assisted by logistics, as they had been against the Romans - the further north the would-be conquerors went, the more their supply lines became stretched and the less hospitable was the climate and the landscape.However, the threat from their southern neighbours was to push them towards a similarly baronial and nationalist future.

Scotland was a part of Norway before it ever achieved nation status in its own right. Indeed for a short period Norway was ruled from Orkney. Around the 1000AD Scotland came into being as a recognised country. Malcolm Canmore made definite attempts to extend and consolidate land under his control. This brought the Scots into conflict with the English for the first time as the Border was pushed South from the Forth to the Tweed and beyond.

After nearly 200 years of harassment and counter-attack, the Scots were finally able to assert their independence as a nation by defeating the army of King Edward 1 of England at the battle of Bannockburn in 1314. This was followed in 1320 by the Declaration of Arbroath: a document comparable to the Magna Carta in establishing ideas of freedom and democracy within a nation state. The declaration also contains a reference to the celtic origins of the Scots that agrees very well with recent evidence about the early settlers.

For several hundred years afterwards, “freedom” would often mean swearing allegiance to the local Lord and hoping for some protection in return. For much of our history, ordinary people would keep their heads down, pay their taxes, and most men would try to avoid being forced into the military. This is not very exciting stuff, so even the invention of writing, and then the printing press, has left little record of the history of the “commoners”.

In spite of the best efforts of the Normans, “history” was left to the powerful families who ruled entire regions, slugging it out in ventures such as the Wars of the Roses to see whether they could get their hands on the nation's crown, its army and its treasury. Like the Romans before them, the Normans remained a colonial elite. They added to the English language rather than replacing it, and they hardly contributed to the English gene pool at all.

Ironically, the Scots aristocracy would increasingly look towards France for support, allowing a whiff of the other “gallic” to float around the growing cities like Edinburgh.

Meanwhile, in the wilder and more inaccessible areas of the land, powerful families ran free of state control. The rievers of the border-lands (both English and Scottish) would raid each other's territory and also otherwise calm areas, causing havoc among the villages, and this cattle-rustling and gangsterism would continue almost through to unification in 1707.

“... for, as long as but a hundred of us remain alive, never will we on any conditions be brought under English rule. It is in truth not for glory, nor riches, nor honours that we are fighting, but for freedom -- for that alone, which no honest man gives up but with life itself.”

Declaration of Arbroath 1320

Along with the growth of the nation state, the Christian church was becoming more organised. Monasteries, originally collectives of hermits, were established by the early Celtic chirch on remote islands, as if to emphasise their other-worldy and spiritual role. As the years went by, Lindisfarne became one of the main centres of European culture with links to the courts of King Alfred in Wessex and the Emperer Charlemagne in Aachen. Unfortunately, Lindisfarne bacame an accessible target for Viking raiders. The hand-wrought Linisfarne Gospels survived the attacks until the late 9th century when the now-pricelass manuscripts were nearly lost at sea by monks fleeing another "smash and grab". The Vikings did not seem to place much value on books.

But monasteries grew in size and wealth, and became important centres (sometimes the only centres) of literacy and learning. In turn this would lead to the establishment of universities: St Andrews University was given its charter in 1410 as a school attached to the Augustinian Priory. It was lucky that this was done, because the Cathedral and the rest of the church establishment was stripped out in 1559 during the Reformation.

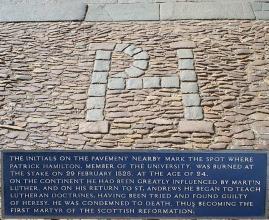

The Reformation in England had started earlier, in 1536, precipitated by Henry the Eight's argument with the Pope over his divorce. For hundreds of years “church and state” had been a valuable counter-balance to absolute power. But now the monasteries were seen to be threatening the state, and the men of the church were widely seen, particularly by poor people, as bloated money-grabbers. Animosity was stirred by protestants such as John Knox. In St Andrews you can see the pavement memorials to protestant “martyrs” with mosaics now showing where their blood soaked into the cobbles. In the Dark Ages, people were fighting and killing each other over land. Now, in a worrying development, they were beginning to fight over ideas.

Click to read the plaque for the Patrick Hamilton memorial.JPG

Click to read the plaque for the George Wishart memorial.JPG

The city and trade

The technologies of metal-working and the Protestant ethic of “work hard and save money” were important foundations of the Industrial Revolution. There were, of course, more to come.

The soclal organisation of the cities began to rival the feudal society of life on the land. The cities and would eventually triumph, even though they were often no larger than the small towns of today. Feudalism was undermined when plague spread throughout Europe with the Black Death of the 1340s and the population was reduced significantly. There was a rapid fall in the supply of people to work on the land and in the manorial houses. This resulted in successful demands for higher wages and, in the case of serfs and villains, some kind of freedom. A labour market was opening up. In turn, this affected the nature of agriculture, which began to turn away from social structures and become more of a “business”, supplying merchants in the cities. Even the peasant could produce a surplus for the market. If not ready for the Industrial Revolution yet, Europe entered a period of new beginnings – the Renaissance.

The medieval cities provided new opportunities for developments in technology and the arts. Craft guilds emerged. As well as self-regulation of their trades, they allowed innovation with skills and materials and provide training centred around small workshops, often clustered in a particular “quarter” of the city.

1695 the Bank of Scotland was founded with the help of William Paterson in Edinburgh. Flushed with his earlier success in founding the Bank of England a few years earlier, Paterson had travelled to the Americas. He became beguiled by travellers' tales of Darien, a wonderful land on the Isthmus of Panama, as told to him by a sailor he met in a bar in London. Returning to Edinburgh, Paterson persuaded the Scottish government that Scotland should not be left behind in establishing colonies in the New World. Unfortunately, England, France and Spain were already fighting over the best bits, so Patterson used his “insider knowledge” to recommend Panama as the place most likely to to provide Scotland with its colonial base. The resulting expedition to “New Caledonia” was both a personal disaster for Patterson, and ultimately a national one. Analysts have estimated that up to a quarter of the money in circulation in Scotland was lost in trying to claim the Central American swamps. Many families lost their life savings. Scotland, first in so many technological advances, had the dubious privilege of being the first nation state to go bust, and was bailed out by the London government through the Act of Union of 1707.

It was probably events like this that led Burns to describe some of his compatriots as “a parcel o' rogues”. It was an eerie parallel with the great banking crisis of 2008, when a similar venture, this time into the virtual swamps of the global financial markets, was to bring down the two major Edinburgh banks, leading to a bail-out by UK taxpayers. (At the time of writing, there is no equivalent to the Act of Union on the horizon.)

The new British Empire was on the rise, with international trade leading to the growth of the great mercantile cities of Liverpool and Glasgow, with tobacco and slavery as early benefactors. We also saw the sucess of our east coast ports such as Hull, with the wool trade providing much of the early investment, as it did in the west. With the arrival of Empire, the textile trade would specialise with cotton in Glasgow and Liverpool and jute in Dundee.

The Jacobite uprising of 1745 was another poorly-led venture to get control of the inexhaustible riches. It finished with the defeat of the Catholics and the French, together with their Scottish supporters at the last military battle fought in our region.

The East West split of Highlands versus Lallands was a marked feature of whether Scots chose to favour Bonnie Prince Charlie or King George’s army led by his son The Duke of Cumberland - still known as "Bloody Cumberland" in Scotland (or "Butcher Cumberland" in polite English society and school textbooks) - who was supported at Culloden’s final victory by many lowland regiments.

The rebellion started in north-west Scotland, and had enough momentum to get as far south as Derby. (In the 1970's an old Derbyshire man told me that he called all Yorkshiremen “scotch rogues”, because some of their ancestors came south with Bonny Prince Charlie). The '45 belonged to an earlier time, Trade was the uprising, and Trade would eventually win.

In spite of being one of the poorer countries in Europe, by 1750 the Scots developed an advanced public education system, part-funded by taxation and the Kirk. With its roots now firmly established, it was to flower as the Age of Reason - the Enlightenment – in Glasgow and Edinburgh. Philosophers such as David Hume reflected on human nature and reasoning, laying the way for widespread application of scientific methods. Adam Smith presented economics as a discipline for the first time and grappled with the underlying philosophy. James Hutton developed the science of geology, and was one of the first to speculate on evolution by natural selection. Writers such as Robert Burns reflected upon human values and a fair society.

Rejecting much of the religious dogma and received wisdom of the time, these free-thinkers looked at life from a humanist, as opposed to a superstitious, point of view. The old orders of politics and trade were questioned and changes proposed, authority itself was challenged. Although this was happening all over Europe, here the emphasis was on an empirical approach, where the world was to be observed closely and progress made by showing what worked.

Alternative Empire?

“What got created - for a brief, dazzling generation during the first quarter of the 19th century - was a non-English British Indian government; perhaps the best the British ever made in Asia. Virtually all of its stars were Scots, Irish or Welsh. The most phenomenally knowledgeable and culturally tolerant of them were Scots like Sir Thomas Munro, Sir John Malcolm and Mountstuart Elphinstone, and a little later James Thomason in the northwest provinces. All took to India the lessons of the Scottish enlightenment, especially the budding sociology of Adam Ferguson and John Millar, in which wise public action had to be grounded on deep local understanding. It was, in fact, just because so many of them felt that English government had so misunderstood and so mistreated their own country that as Britons they were determined not to repeat the mistake in Asia. Many of them became authorities on the minutiae of the history, law and agrarian economics of the territories under their rule.

"To act effectively meant knowing in depth the states and societies with which one was dealing. So Malcolm wrote extensively on the Sikhs, and published The History of Persia (1815). Elphinstone, who had fought with the Maratha princes, produced the encyclopedic Report on the Territories Conquered from the Paishwa (1821). And those writings were often strikingly free of the stereotypes about 'anarchy' that coloured the work of the later Victorians. Elphinstone was at pains to portray Mughal rule as a golden age of peaceful relations between Muslims and Hindus. “

Simon Schama “A History of Britain” Vol 3

Looking back, it is easy to underestimate the freshness of the thinking and the considerable impact that these ideas have had on our cities of today. Their ideas may still be the subject of intense debate, but it is easy to forget that they were dreamed up an a very different society than the one that we live in. Much of our world was foreseen by the enlightenment writers. I wonder what they would write if we could bring them back today, so they could see what has worked, and what has not, and look again with their keen eyes at the sprawl of modern civilisation.

For those (particularly the Glaswegians) who see the work of Francis Hutcheson as its initiator, our northern branch of the Enlightenment had its beginnings at Glasgow University. But it was in Edinburgh that the city itself began to function as a university, such was the concentration of talent. Having failed in the Darien venture, Edinburgh was now to export its ideas across the world, with phenomenal success.

Empire and industry

Up to the 1750's, clothing and other goods were produced by cottage industries, there were no factories, or the “mills” to drive them. Weavers worked at home and pack horses transported the rolls of cloth and the finished goods. Woollen cloth was an important export by 1400. Water power along the Tweed and Clyde, and in the Pennines, saw the beginnings of mechanisation. Flax was widely grown, and the linen produced was important in the family and village economy.

The drive towards the mechanisation of weaving began with John Kay's flying shuttle in 1733 and, for spinning, with the spinning jenny of James Hargreaves 1764. This was quickly followed by Richard Arkwright's spinning mule at Cromford, Derbyshire in 1771 and by the power loom of Edmund Cartwright 1785. The motive power for Cromford mill was merely running water, but the factory was the beginning of a new age.

Coal has been mined in the region since the Roman invasion. “Sea coal” was freely available from the Northumbrian coast and the coast further north from around 1200. Most of the regions south of the Highlands have coal deposits and coal was valued for metal-working because it has a higher heat content than charcoal. Coal was probably discovered in some of the numerous quarries and metal extraction pits that pock-marked the landscape before the large-scale disruption of the Industrial Revolution. The first proper coal mine was dug in 1575 under the Firth of Forth, on the Fife side at Culross, so contributing to “Auld Reekie” just across the water. Demand for coal was still relatively low, and the industry would have to wait 200 years or so for the investment, and the technology, for deep mines.

While at Glasgow University in 1769, James Watt came up with a radical improvement to Thomas Newcomen's steam engine, used since 1712 for pumping out flooded mine-workings. Watt's improvements gave a step-change in power and efficiency. In 1775 he established a company to manufacture steam engines with the businessman and metal-basher Matthew Boulton. Mills could now be built anywhere, as long as they could get the coal.

Iron ore was readily available and the first efficient blast furnace was established at Furness in the Lake District in 1711. The furnace was fuelled by charcoal, but a few years later a coke-fired furnace was in operation at Little Clifton, not so far away at Workington. John “Iron mad” Wilkinson was born there when his father was working as pot-founder. He went on to be a major shareholder in Abraham Derby's Iron Bridge and to launch the first iron barge. “Iron Mad” was approached by Boulton and Watt for help with the cylinders for their new steam engine and obliged by developing a suitable manufacturing technique. All manner of metals and alloys were now available, and the forging and machining techniques to shape them. The manufacture of powerful engines was now possible.

In 1757 there was the first-ever recorded cotton auction in Liverpool. By 1771, cotton was imported through Glasgow. This rapidly replaced the weaving of local wool and linen in Lancshire and the Clyde valley, because the damper climate was more suitable for cotton-spinning. Raw materials were streaming into our region's ports from the colonies. And shipbuilding was keeping pace with new technology. Glasgow, in particular, would use its mercantile base and its education system to forge itself into a world centre of expertise in engines and metal structures, leading to a pre-eminence in power station, locomotive and ship-building that lasted until the 1970's.

The Industrial Revolution was up and running. All that was missing was a supply of plentiful “hands” to work in the “mills”. Clearances and enclosures of common land helped, the people moved out and the sheep moved in. Agriculture increased as kitchen gardens were abandoned and commons enclosed. Monoculture brought about famine and further displacement. Those who did not seek a new life in the colonies were pushed into the cities.

Some artisan families rebelled against the future, seeing that work and livelihood was being removed from home and family. In the name of an early activist, Ned Ludd, they smashed mechanical “frame” looms in factories across West Yorkshire and Lancashire, particularly those owned by the new class of “free market” capitalists. There was a ruthless response from the government, as there would be a few years later in 1819, at St Peters Field in Manchester, near where the civic buildings stand today. Over 50,000 people had gathered at a political meeting to call for the right to vote at parliamentary elections. In “dispersing” the crowd, the cavalry managed to kill 18 people and injure hundreds of others, including women and children. King Ludd would have to give way to King Cotton and King Coal.

Social struggles continued, but nothing could stop the growth of cities. Industry was becoming widespread but concentrated in great powerhouses that the world had never seen or experienced before. Manchester's population doubled between 1801 and 1821 and nearly doubled again in the next twenty years, reaching half a million people by 1881. At the beginnings of the Industrial Revolution, our cities were the size of ordinary towns today. Fifty years later they were almost unimaginable, whether looking forward or, like us, looking back. There was little thought and attention to the quality of life for most of those unfortunate people who were living in “third world” slums of disgusting deprivation. Concerned observers such as Mary Gaskell and Friedrich Engels have written extensively of their experiences, sometimes in distressing detail. It would take the “city fathers” some time to react, although the emergence of Victorian civic pride would begin to make the cities habitable.

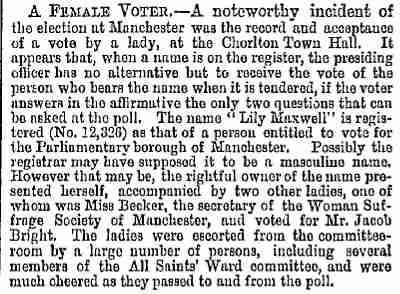

“In a Manchester by-election in November1867 a widowed shopkeeper, Lily Maxwell, became the first woman to cast a vote in a British election. She was only on the register as the result of a clerical error;, but once she was discovered by Jacob Bright and the suffrage campaigner Lydia Becker, they were determined that she should go through with it. Escorted to the poll, she cast her vote to a round of loud applause. An obviously disconcerted pioneer, Lily must none the less have had a great deal of gumption, not to mention sympathy with the aim of the suffragists (who had been campaigning peacefully for the vote since 1866), to play her part in what became an elaborately staged event. A surviving photograph certainly suggests a woman with a good deal of flinty determination.

“Like the Chartist Land Company settler Ann Wood, Lily Maxwell was a classic example of gritty Scottish thrift: an ex-domestic servant who had saved enough to become a shopkeeper, and who paid the respectable weekly rent of 6 shillings and 2 pence for her place in Ludlow Street, a mix of artisan and lower middle-class, two-up, two-down brick dwellings. When her case became famous - or, to the conservative press, shocking - Lydia Becker wrote a dignified letter to the Times on 3 December 1867, describing her as a model voter of the kind intended to be emancipated by the Reform Act, 'á widow who keeps a small shop in a quiet street in Manchester. She supports herself and pays her own rates and taxes out of her own earnings. She has no man to influence or be influenced by, and she has very decided political principles, which determined her vote for Mr Jacob Bright at the recent election.' As a result of the publicity around Lily Maxwell's vote, Lydia Becker was able to open a register to enrol qualified women householders. By the end of 1868,her list numbered 13,000. “

Simon Schama “A History of Britain” Vol 3

Artisan families in Lancashire circa 1775

“The workshop of the weaver was a rural cottage, from which when he was tired of sedentary labour he could easily sally forth into his little garden, and with the spade or the hoe tend its culinary productions. The cotton wool which was to form his weft was picked clean by the fingers of his younger children, and was carded and spun by the older girls assisted by his wife, and the yarn was woven by himself assisted by his sons. When he could not procure within his family a supply of yarn adequate to the demands of his loom, he had recourse to the spinsters of his neighbourhood.”

A. Ure, Cotton Manufacture of Great Britain (1836)

“Their dwellings and small gardens clean and neat - all the family well clad - the men each with a watch in his pocket and the women dressed in their own fancy - the church crowded to excess every Sunday - every house well furnished with a clock in elegant mahogany or a fancy case - handsome services in Staffordshire ware." Many cottage families had their cow, paying so much for the summer's grass, and about a statute acre of land laid out for them in some croft or corner, which they dressed up as a meadow for hay in the winter.”

William Radcliffe Origin of the New System of Manufactures (1828)

Manchester in the early 19th century

"The dwellings of the labouring manufacturers are in narrow streets and lanes, blocked up from light and air, crowded together because every inch of land is of such value that room for light and air cannot be afforded them. Here in Manchester, a great proportion of the poor lodge in cellars, damp and dark, where every kind of filth is suffered to accumulate because no exertions of domestic care can ever make such homes decent."

Robert Southey 1808

"And such a district exists in the heart of the second city of England, the first manufacturing city of the world. If any one wishes to see in how little space a human being can move, how little air - and such air! - he can breathe, how little of civilisation he may share and yet live, it is only necessary to travel hither."

Friedrich Engels

The Condition of the Working Class in England in 1844

With the rapid spiralling of engineering development, Leeds rapidly changed from a wool-trade town into "the city that makes everything". The 1801 census gives the population of Leeds as 30,000. By 1851 it was over 100,000. It took the cholera outbreak of 1832 to bring about the basics of sanitation. But a further outbreak of cholera in 1849 killed over 2000 people. As elsewhere, the city fathers were slow to apply their engineering capital and expertise to improve the life of the (largely) miserable workforce.

Most readers will be able to pick up the story from here. Some commentators date our industrial decline from the early 1900s with the beginnings of globalisation (including global war). Around 1950, almost broken by a defensive war against another would-be empire, Britain began quietly to change its Empire into a Commonwealth of Nations, and introduce the Welfare State at home. Neither would contribute to maintaining free-market industrial wealth-creation, but now we found oil and gas in the North Sea, so we still had some time to work out what to do …...

Empire - the beginning of the end?

In 1931, around 10,000 workers were unemployed in Darwen because of the Indian manufactured-cotton boycott. Mahatma Gandhi was in London, and received an invitation from the owners of Greenfield Mill to visit the cotton workers in the Lancashire town.

"I am overwhelmed by the affection shown to me in Lancashire. The poverty I have seen distresses me, and it distresses me further to know that, in this unemployment, I also had some kind of share."

Gandhi

Read Lancashire Evening Telegrapph article by Catherine Pye

Gandhi comes to visit the mill workers of Darwen, Septemeber 1931

All change

Lately, things have gone rather quiet in our part of the world. Our industrial journey seems to have reached the end of the line. Looking around, we see a dreary monoculture in both town and country. The protestant work ethic of “working and saving” seems to have changed to “getting and spending” - perhaps we need another ethic now? As in the Bronze Age, 4000 years ago, nation states continue to jostle with each other over resources and new technology brings new weapons.

Now Nature, too threatens our precious cities with a potential rise in sea-levels. Many of our major urban areas are at low elevations; for good reasons, as those of us who live among the hills will know. If sea level rise does happen, there will be a considerable displacement of our population into the uplands, as the Greenhouse Britain scenarios show.

The Hadley Centre's predictions for climate change by 2050 are not too alarming. There is still significant rain falling and summer temperatures are hot, but not unbearable. Many commentators believe that our region will get off lightly.

But one nagging doubt is that the loss of the Atlantic conveyor current would bring much colder, Canadian-style winters.

If we are to be spared the worst effects of climate change, then it is people we will have to deal with, rather than Nature. Our islands have a history of colonisation by people wanting new land, a new start. What do we do when the next wave comes?

Guides to Climate Change in North Britain

Greenhouse Britain

http://greenhousebritain.greenmuseum.org/downloads/

Hadley Centre

http://www.metoffice.gov.uk/climatechange/guide/ukcp/map/

Problems in the Atlantic?

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Shutdown_of_thermohaline_circulation

It is little use complaining that we have got ourselves into a mess. Sooner or later we must clear up the mess, and move on. In working out what to do, I like to draw on the positive characteristics of our ancestors. How did we achieve the wonders of the modern age? Through their ingenuity, foresight, hard work and canniness. Exactly those qualities that live on in us.

We can claim that the Industrial Revolution and the Age of Globalisation began in our region. Perhaps we can take some responsibility for that, and sow the seeds of a further Enlightenment to occupy the hands and minds of our expanding population.

We have had our Empire, been there, done that; now it's time to try something else. As old certainties dissolve, we can turn our industry towards living peaceably in this wonderful landscape.