You are here

Empire and industry

Up to the 1750's, clothing and other goods were produced by cottage industries, there were no factories, or the “mills” to drive them. Weavers worked at home and pack horses transported the rolls of cloth and the finished goods. Woollen cloth was an important export by 1400. Water power along the Tweed and Clyde, and in the Pennines, saw the beginnings of mechanisation. Flax was widely grown, and the linen produced was important in the family and village economy.

The drive towards the mechanisation of weaving began with John Kay's flying shuttle in 1733 and, for spinning, with the spinning jenny of James Hargreaves 1764. This was quickly followed by Richard Arkwright's spinning mule at Cromford, Derbyshire in 1771 and by the power loom of Edmund Cartwright 1785. The motive power for Cromford mill was merely running water, but the factory was the beginning of a new age.

Coal has been mined in the region since the Roman invasion. “Sea coal” was freely available from the Northumbrian coast and the coast further north from around 1200. Most of the regions south of the Highlands have coal deposits and coal was valued for metal-working because it has a higher heat content than charcoal. Coal was probably discovered in some of the numerous quarries and metal extraction pits that pock-marked the landscape before the large-scale disruption of the Industrial Revolution. The first proper coal mine was dug in 1575 under the Firth of Forth, on the Fife side at Culross, so contributing to “Auld Reekie” just across the water. Demand for coal was still relatively low, and the industry would have to wait 200 years or so for the investment, and the technology, for deep mines.

While at Glasgow University in 1769, James Watt came up with a radical improvement to Thomas Newcomen's steam engine, used since 1712 for pumping out flooded mine-workings. Watt's improvements gave a step-change in power and efficiency. In 1775 he established a company to manufacture steam engines with the businessman and metal-basher Matthew Boulton. Mills could now be built anywhere, as long as they could get the coal.

Iron ore was readily available and the first efficient blast furnace was established at Furness in the Lake District in 1711. The furnace was fuelled by charcoal, but a few years later a coke-fired furnace was in operation at Little Clifton, not so far away at Workington. John “Iron mad” Wilkinson was born there when his father was working as pot-founder. He went on to be a major shareholder in Abraham Derby's Iron Bridge and to launch the first iron barge. “Iron Mad” was approached by Boulton and Watt for help with the cylinders for their new steam engine and obliged by developing a suitable manufacturing technique. All manner of metals and alloys were now available, and the forging and machining techniques to shape them. The manufacture of powerful engines was now possible.

In 1757 there was the first-ever recorded cotton auction in Liverpool. By 1771, cotton was imported through Glasgow. This rapidly replaced the weaving of local wool and linen in Lancshire and the Clyde valley, because the damper climate was more suitable for cotton-spinning. Raw materials were streaming into our region's ports from the colonies. And shipbuilding was keeping pace with new technology. Glasgow, in particular, would use its mercantile base and its education system to forge itself into a world centre of expertise in engines and metal structures, leading to a pre-eminence in power station, locomotive and ship-building that lasted until the 1970's.

The Industrial Revolution was up and running. All that was missing was a supply of plentiful “hands” to work in the “mills”. Clearances and enclosures of common land helped, the people moved out and the sheep moved in. Agriculture increased as kitchen gardens were abandoned and commons enclosed. Monoculture brought about famine and further displacement. Those who did not seek a new life in the colonies were pushed into the cities.

Some artisan families rebelled against the future, seeing that work and livelihood was being removed from home and family. In the name of an early activist, Ned Ludd, they smashed mechanical “frame” looms in factories across West Yorkshire and Lancashire, particularly those owned by the new class of “free market” capitalists. There was a ruthless response from the government, as there would be a few years later in 1819, at St Peters Field in Manchester, near where the civic buildings stand today. Over 50,000 people had gathered at a political meeting to call for the right to vote at parliamentary elections. In “dispersing” the crowd, the cavalry managed to kill 18 people and injure hundreds of others, including women and children. King Ludd would have to give way to King Cotton and King Coal.

Social struggles continued, but nothing could stop the growth of cities. Industry was becoming widespread but concentrated in great powerhouses that the world had never seen or experienced before. Manchester's population doubled between 1801 and 1821 and nearly doubled again in the next twenty years, reaching half a million people by 1881. At the beginnings of the Industrial Revolution, our cities were the size of ordinary towns today. Fifty years later they were almost unimaginable, whether looking forward or, like us, looking back. There was little thought and attention to the quality of life for most of those unfortunate people who were living in “third world” slums of disgusting deprivation. Concerned observers such as Mary Gaskell and Friedrich Engels have written extensively of their experiences, sometimes in distressing detail. It would take the “city fathers” some time to react, although the emergence of Victorian civic pride would begin to make the cities habitable.

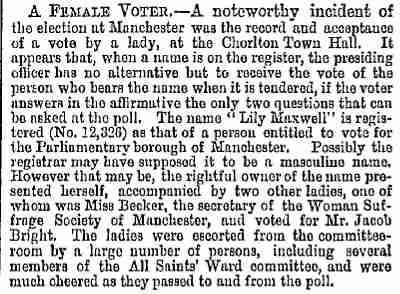

“In a Manchester by-election in November1867 a widowed shopkeeper, Lily Maxwell, became the first woman to cast a vote in a British election. She was only on the register as the result of a clerical error;, but once she was discovered by Jacob Bright and the suffrage campaigner Lydia Becker, they were determined that she should go through with it. Escorted to the poll, she cast her vote to a round of loud applause. An obviously disconcerted pioneer, Lily must none the less have had a great deal of gumption, not to mention sympathy with the aim of the suffragists (who had been campaigning peacefully for the vote since 1866), to play her part in what became an elaborately staged event. A surviving photograph certainly suggests a woman with a good deal of flinty determination.

“Like the Chartist Land Company settler Ann Wood, Lily Maxwell was a classic example of gritty Scottish thrift: an ex-domestic servant who had saved enough to become a shopkeeper, and who paid the respectable weekly rent of 6 shillings and 2 pence for her place in Ludlow Street, a mix of artisan and lower middle-class, two-up, two-down brick dwellings. When her case became famous - or, to the conservative press, shocking - Lydia Becker wrote a dignified letter to the Times on 3 December 1867, describing her as a model voter of the kind intended to be emancipated by the Reform Act, 'á widow who keeps a small shop in a quiet street in Manchester. She supports herself and pays her own rates and taxes out of her own earnings. She has no man to influence or be influenced by, and she has very decided political principles, which determined her vote for Mr Jacob Bright at the recent election.' As a result of the publicity around Lily Maxwell's vote, Lydia Becker was able to open a register to enrol qualified women householders. By the end of 1868,her list numbered 13,000. “

Simon Schama “A History of Britain” Vol 3

Artisan families in Lancashire circa 1775

“The workshop of the weaver was a rural cottage, from which when he was tired of sedentary labour he could easily sally forth into his little garden, and with the spade or the hoe tend its culinary productions. The cotton wool which was to form his weft was picked clean by the fingers of his younger children, and was carded and spun by the older girls assisted by his wife, and the yarn was woven by himself assisted by his sons. When he could not procure within his family a supply of yarn adequate to the demands of his loom, he had recourse to the spinsters of his neighbourhood.”

A. Ure, Cotton Manufacture of Great Britain (1836)

“Their dwellings and small gardens clean and neat - all the family well clad - the men each with a watch in his pocket and the women dressed in their own fancy - the church crowded to excess every Sunday - every house well furnished with a clock in elegant mahogany or a fancy case - handsome services in Staffordshire ware." Many cottage families had their cow, paying so much for the summer's grass, and about a statute acre of land laid out for them in some croft or corner, which they dressed up as a meadow for hay in the winter.”

William Radcliffe Origin of the New System of Manufactures (1828)

Manchester in the early 19th century

"The dwellings of the labouring manufacturers are in narrow streets and lanes, blocked up from light and air, crowded together because every inch of land is of such value that room for light and air cannot be afforded them. Here in Manchester, a great proportion of the poor lodge in cellars, damp and dark, where every kind of filth is suffered to accumulate because no exertions of domestic care can ever make such homes decent."

Robert Southey 1808

"And such a district exists in the heart of the second city of England, the first manufacturing city of the world. If any one wishes to see in how little space a human being can move, how little air - and such air! - he can breathe, how little of civilisation he may share and yet live, it is only necessary to travel hither."

Friedrich Engels

The Condition of the Working Class in England in 1844

With the rapid spiralling of engineering development, Leeds rapidly changed from a wool-trade town into "the city that makes everything". The 1801 census gives the population of Leeds as 30,000. By 1851 it was over 100,000. It took the cholera outbreak of 1832 to bring about the basics of sanitation. But a further outbreak of cholera in 1849 killed over 2000 people. As elsewhere, the city fathers were slow to apply their engineering capital and expertise to improve the life of the (largely) miserable workforce.

Most readers will be able to pick up the story from here. Some commentators date our industrial decline from the early 1900s with the beginnings of globalisation (including global war). Around 1950, almost broken by a defensive war against another would-be empire, Britain began quietly to change its Empire into a Commonwealth of Nations, and introduce the Welfare State at home. Neither would contribute to maintaining free-market industrial wealth-creation, but now we found oil and gas in the North Sea, so we still had some time to work out what to do …...

Empire - the beginning of the end?

In 1931, around 10,000 workers were unemployed in Darwen because of the Indian manufactured-cotton boycott. Mahatma Gandhi was in London, and received an invitation from the owners of Greenfield Mill to visit the cotton workers in the Lancashire town.

"I am overwhelmed by the affection shown to me in Lancashire. The poverty I have seen distresses me, and it distresses me further to know that, in this unemployment, I also had some kind of share."

Gandhi

Read Lancashire Evening Telegrapph article by Catherine Pye

Gandhi comes to visit the mill workers of Darwen, Septemeber 1931